Block ciphers and modes of operation

Since ancient times, man has been concerned that only the recipient of the message, and not an evil third party, can know the information it contains. From the ancient Hebrews who developed Atbash encryption, a primitive monoalphabetic substitution cipher, Spartans who used transposition cipher of the scytale, or even the Romans with the famous Caesar cipher; to current encryption much more complex and secure.

Precisely we will talk today about a set of these modern algorithms.

Block ciphers

We can classify all current cryptography into three large families based on the characteristics of their key. Symmetric encryption, where the key used to encrypt and decrypt is the same. Asymmetric, in which the key to encrypt is different from the one to decrypt (there are a pair of keys). And cryptography without a key, which forms the basis of the digital signature.

Today’s topic focuses on a range of algorithms belonging to the first family, symmetric encryption, called block ciphers.

Divide et impera

One way to encrypt information is to divide the problem into several parts. This is what block encryption algorithms do; they divide information into blocks of a set length and perform their magic on them. As the size of the information to be encrypted is not always a multiple of the block size, padding is added at the end of the message. In case it was a multiple of the block size, padding is added too. In this way, by deciphering and eliminating the padding, the original message is recovered.

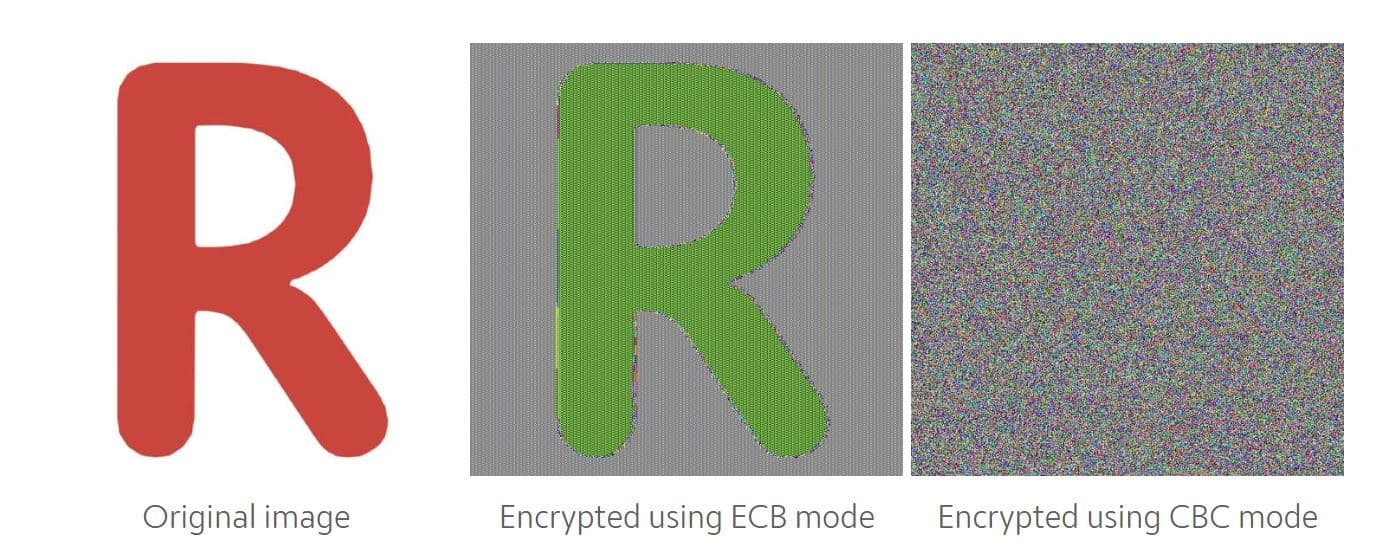

However, proceeding block by block (ECB mode) is not always the best idea. When the blocks are equal, the result of the cipher will also be the same for all of them, that is a big problem in very redundant messages (for example a photo with many equal pixels). Let’s see it with the blog’s favicon.

For this reason the modes of operations appears.

ECB mode of operation

Electronic Code Book (ECB) is the simplest one. In fact, we have already explained it. Each message’s block is encrypted separately and that provokes the problem above mentioned.

If \( E(\cdot) \) is the cipher function for encrypt, \( D(\cdot) \) is the cipher function for decrypt, \( P_i \) and \( C_i \) are the i-th block of the plaintext and ciphertext respectively, and \( k \) is the key.

Then: \( C_i = E(P_i, k) \) and \( P_i = D(C_i, k) \).

In an easy and visual way:

If an error occurs during the transmission of the ciphertext, the message will only be altered in a block.

CBC mode of operation

From here things get interesting, now we want the ciphertext to seem as random as possible.

In the Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) mode of operation, an initialization vector \( IV \) is used. That vector will be XORed with the plaintext, the result is encripted generating the ciphertext corresponding to that block and also used as initialization vector for the next block. Basically is encrypting the plaintext with a pseudo one-time pad and later encrypt it with the proper function. In this way, when chaining the encryption, the same blocks will be encrypted differently offering a great security.

For encrypt: \( C_0 = E(P_0 \oplus IV, k) \); \( C_{i} = E(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}, k) \)

and for decrypt: \( P_0 = D(C_0, k) \oplus IV \); \( P_{i} = E(C_i, k) \oplus P_{i-1}\)

As an scheme:

If an error occurs during transmission (a single bit), the block corresponding to the error will be completely lost and there will be a minimum error in the next block.

PCBC mode of operation

Propagating Cipher Block Chaining (PCBC) was designed to cause small changes in the ciphertext to propagate indefinitely when decrypting, each block of plaintext is XORed with both the previous plaintext block and the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted.

So now \( C_0 = E(P_0 \oplus IV, k) \); \( C_{i} = E(P_i \oplus P_{i-1} \oplus C_{i-1}, k) \)

\( P_0 = D(C_0, k) \oplus IV \); \( P_{i} = E(C_i, k) \oplus P_{i-1} \oplus C_{i-1} \)

CFB mode of operation

In the Cipher Feedback (CFB) mode is also used an initialization vector \( IV \), but now the result of encrypting the initialization vector is XORed with the plaintext to generate the ciphertext block. Later, this result is used as initialization vector for the next block. This is full equivalent to encrypt the plaintext with an one-time pad.

\( C_0 = E(IV, k) \oplus P_0 \); \( C_{i} = E(C_{i-1}, k) \oplus P_{i} \)

\( P_0 = E(IV, k) \oplus C_0 \); \( P_{i} = E(C_{i-1}, k) \oplus C_{i} \)

Better seen in an scheme:

Then if an error occurs during the transmission, it will provoke a minimal error in the actual block, but the complete loss of the next one.

OFB mode of operation

The Output Feedback (OFB) mode is equal as CFB mode but the result of encrypting the initialization vector is not XORed with the plaintext. With this small change, we achieve that if an error occurs during the transmission, it only will provoke a minimal error in the actual block without affecting the following ones.

\( I_0 = IV \);

\( I_i = E(I_{i-1}, k) \)

\( C_i = E(I_{i}, k) \oplus P_i \)

\( P_i = E(I_{i}, k) \oplus C_i \)

CTR mode of operation

Like in OFB mode, in Counter (CTR) mode we generate a one-time pad. But now we achieve it encrypting the value of a counter \( V_i \) that is increased in each block. For security reasons the counter starts at a non-zero value. Obviously, errors are propagated as in OFB.

\( C_i = E(V_i, k) \oplus P_i \)

\( P_i = E(V_i, k) \oplus C_i \)

Better seen in an scheme:

As an honorable mention, we have the Galois Counter Mode (GCM), which is a special case of counter mode with differences. First, it starts at zero, and finally, it also calculates a message authentication code (MAC) that will be used to check that the ciphertext has not been altered in the transmission.